It may be self-evident but a herbarium is a collection of preserved plant samples that are usually dried and pressed, but may also be stored "pickled" in jars. (Not to be confused with a "herpetarium". If you find yourself in front of a historic-looking building at the St. Louis Zoo and aren't reading carefully when you walk in to see the preserved plants, you'll be in for a surprise!)

Although this was a day of self-guided touring, there were plenty of MBG employees (and volunteers?) to ensure you saw everything. As I entered the 2nd floor I immediately headed toward the activity...

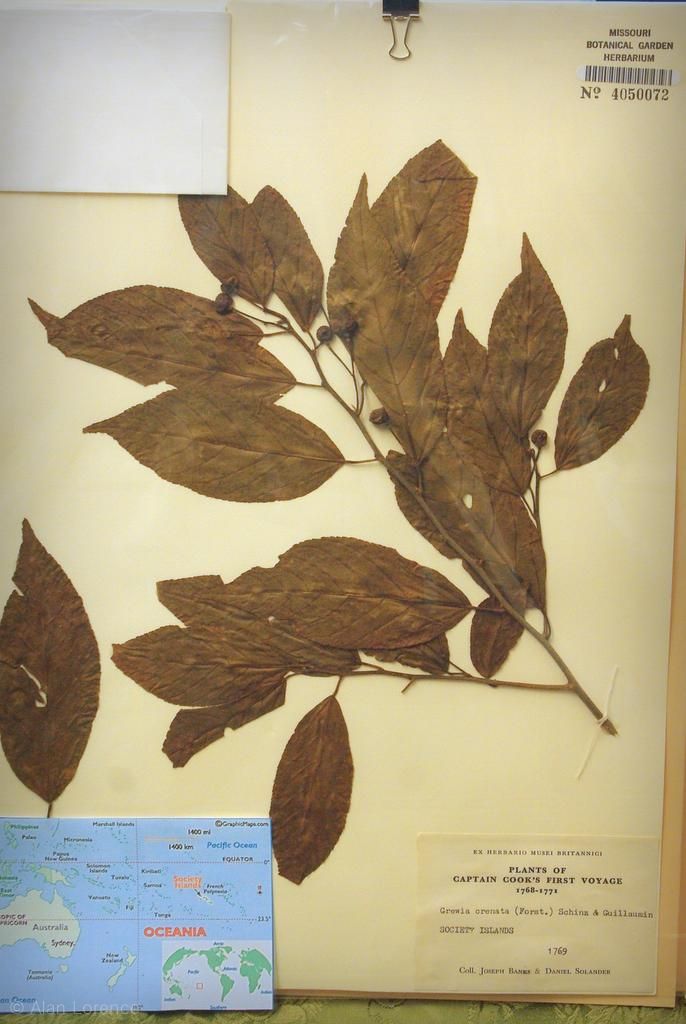

...but then heard somebody in front of me get asked "did you see the first room already?" -- so I turned around to see that I was indeed walking right past said room, and it contained several herbarium samples:

There was quite a bit of history in this room, not only with samples from the 1800's...

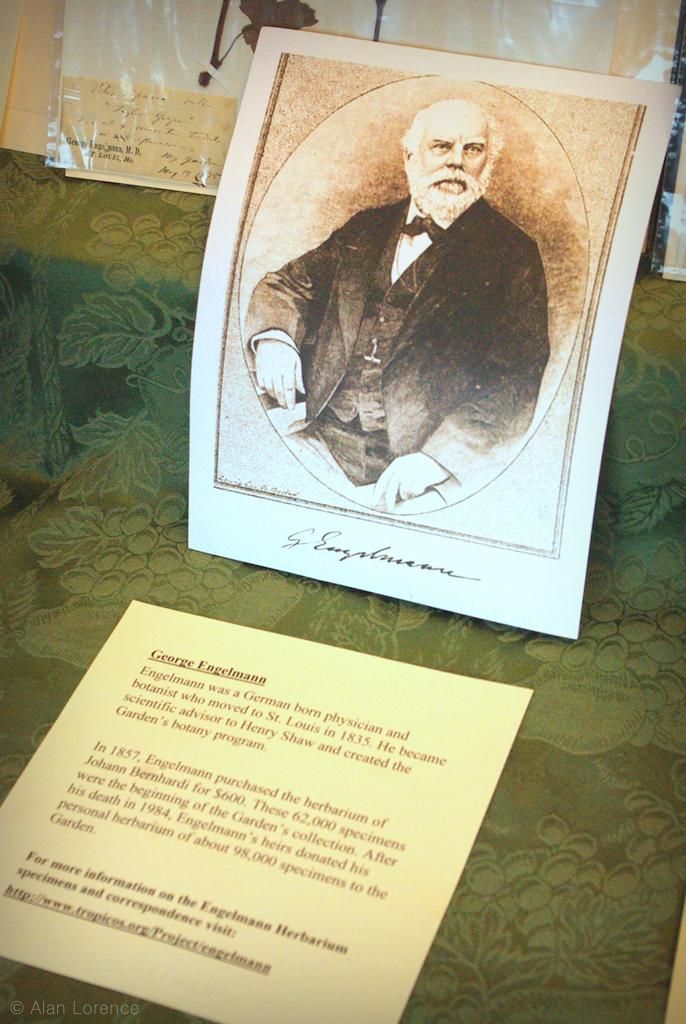

...and information about the collection's origins...

...but they also had on display their oldest specimen, dated 1750 (if I remember correctly):

What struck me was that if you ignored the notations and looked at the specimens alone, there's really no visible difference between a plant collected 150 years ago and one collected in 2011. Moisture and insects are the main enemies here, although old-time non-inert glues and inks cause issues too I learned.

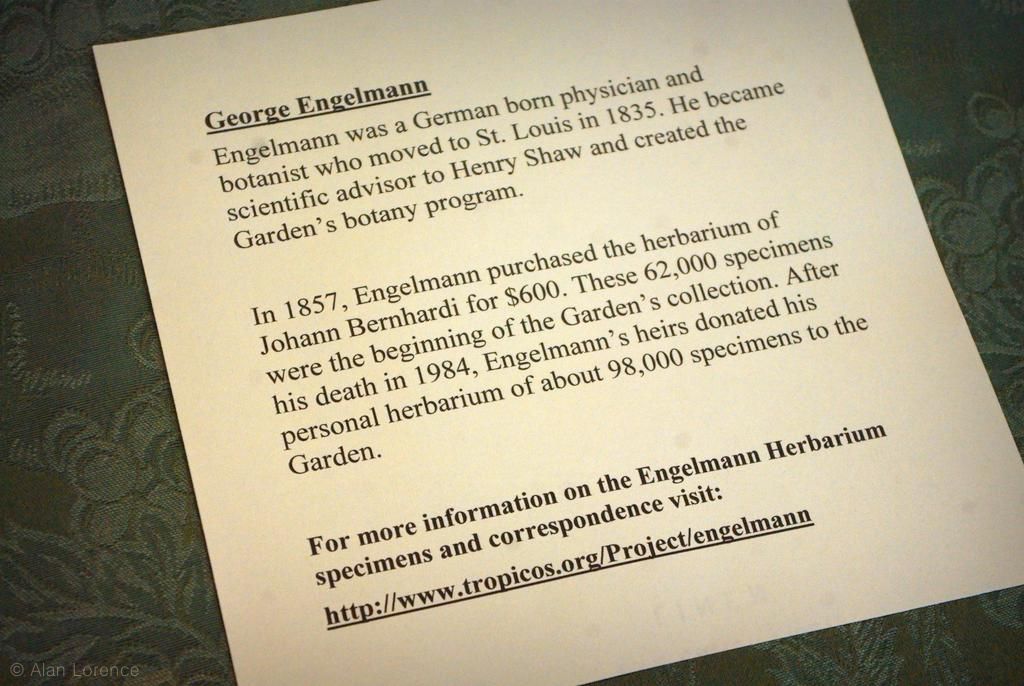

In case you missed it in the image above, here's how the collection got started:

Since $600 in 2014 terms is about $17,000, it was an amazing bargain for 62,000 specimens!George Engelmann was a German born physician and botanist who moved to St. Louis in 1835. He became scientific advisor to Henry Shaw and created the Garden's botany program.In 1857, Engelmann purchased the herbarium of Johann Bernhardi for $600. These 62,000 specimens were the beginning of the Garden's collection. After his death in 1984 (probably 1894?), Engelmann's heirs donated his personal herbarium of about 98,000 specimens to the Garden.

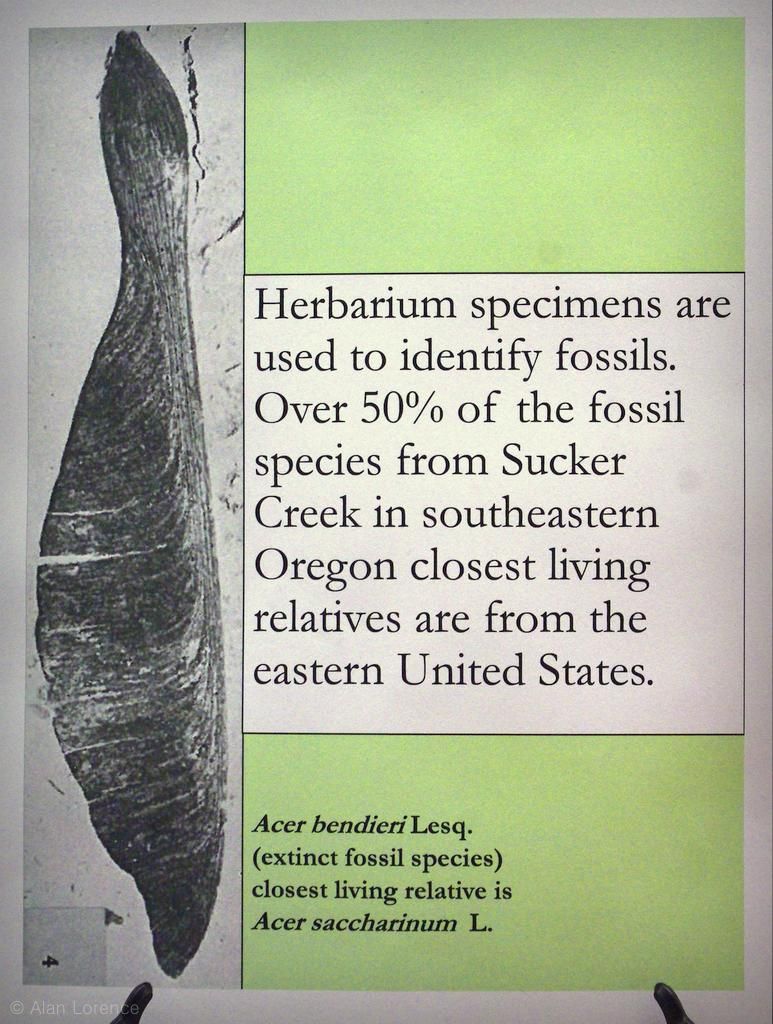

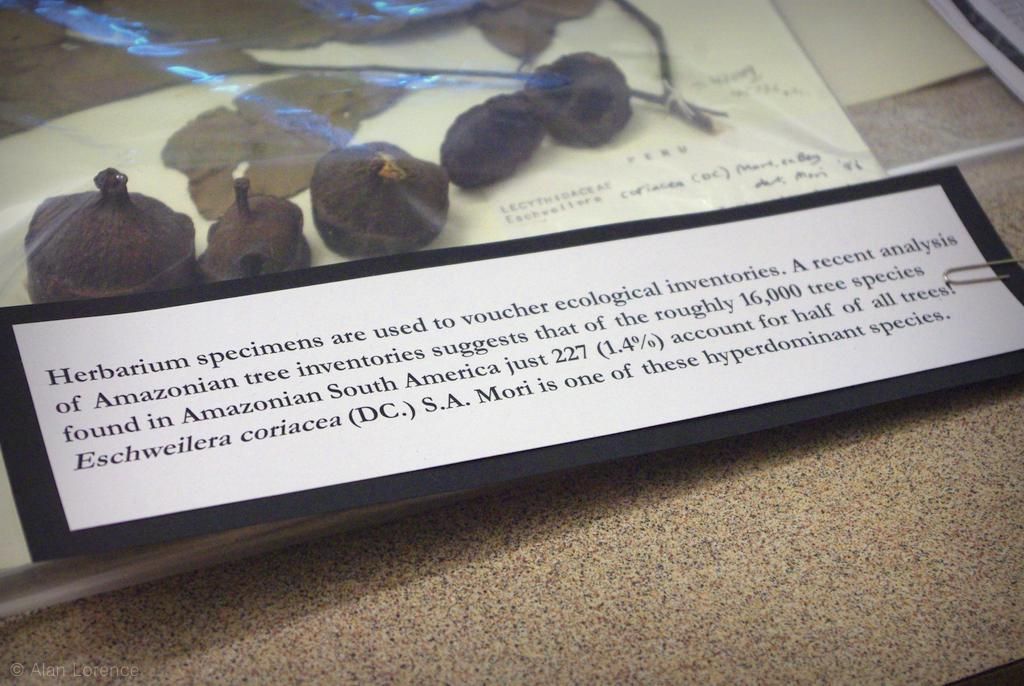

After seeing those samples, it was on to the first display table that answered the question: How is a herbarium used?

Some answers:

At this point I was really quite curious about the more awkward specimens. Sure it's easy enough to press a few leaves from small plants, but what about larger specimens, or things like coconuts? The next couple of samples emphasized this for me:

My questions would soon be answered, as the next table was a display of specimen mounting procedures:

Things I learned: the leaves are attached first using acid-free glue and left to dry overnight. The stems are then attached the next day using dental floss and strips of linen tape. Each specimen sheet has a label of course, but also a small envelope to contain any "fragments" -- parts that break off.

I was quite curious about all aspects of this procedure so also found out that each worker has a quota of 40 samples each day. Some of the work is mounting new samples, but they also do repair to samples that were loaned out or just have a bit of age-related damage.

(I just realized that I'm not going to be able to cover the entire 2nd floor visit in a single post, so I'll end today talking about these samples.)

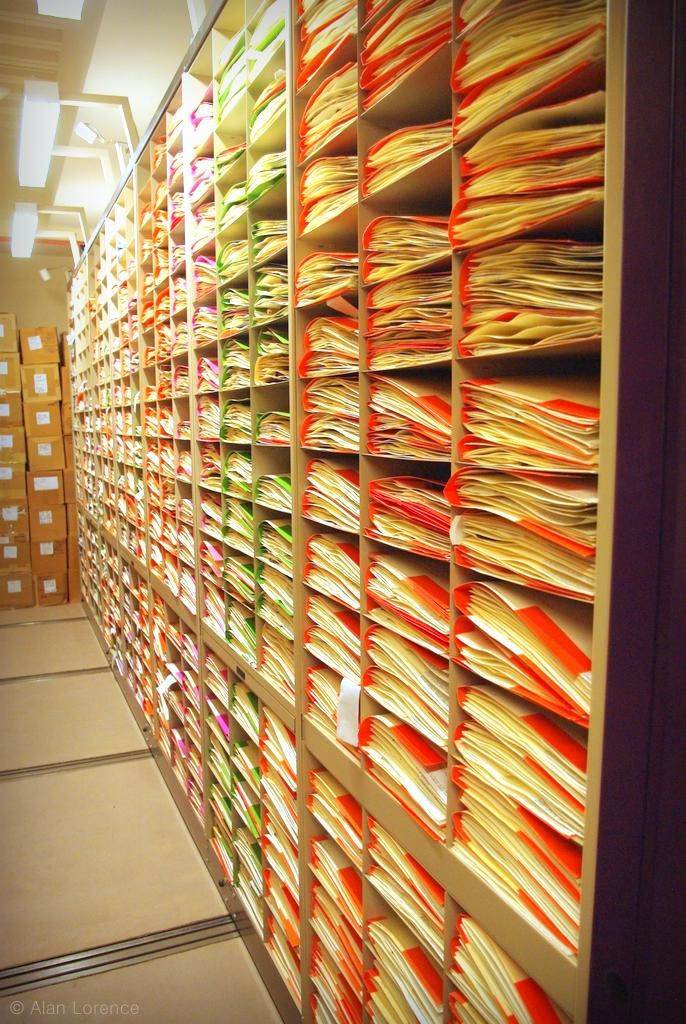

What happens to the samples after they're mounted? They're placed into a paper envelope -- the plastic covers are only used to protect the specimens that are on display -- and then they're put into a folder and then a cubby:

About 30-40 samples go into a cubby, although I'm sure it depends upon the type/size of the samples.

Did I mention that the MBG herbarium is huge? With over 6.5 million samples, it's the 2nd largest in the US, and 5th or 6th largest in the entire world.

That's a lot of cubbies!

And a lot of shelves:

Earlier in the day I heard somebody talking about putting samples into the "compactor". At the time I thought that was the name for what pressed the samples, making them flat for mounting. Here I learned what the "compactor" actually was: the storage space. Makes more sense.

I've learned a lot already, but there is much more to come...

.

These posts keep getting more and more interesting & I'm really enjoying your visit!

ReplyDeleteI work at MBG and volunteered for the open house. I'm so glad that you liked it and that you are doing us the favor of creating such a wonderful write-up with superb photos! Also, your blog software wisely suggested that I would like to see some stories about the cats - awwww, what little beauties they are!

ReplyDeletePeter: glad you're enjoying it!

ReplyDeleteAnon: This was a very informative event and I'm glad I did not miss it. I'm very happy to share -- thank everyone who was involved! (The cats are not so cute and small, but a lot more annoying now.)

Fascinating! Each preserved specimen is history stored away. Amazing how well they last when the process looks so simple and even primitive but actually is very effective and stands the test of time.

ReplyDelete